Back: Tiaki Ormsby (PRS committee member), Mihi Davis-Uerata, Aramoana Davis-Uerata, Kevin Christie (PRS Chair), Gerry Kessels (PRS committee member) Front: Reasha Pye (artist) with baby Saige, Maia Davis-Uerata. Photo credit: Clare St Pierre

The story of kōkako at Pirongia maunga is being brought to life with two murals at the envirocentre in Pirongia Village.

Waipā artist Reasha Pye secured funding from Waipā Creative Communities for the murals. One features a kōkako, feeding on Pirongia and the other a night scene featuring pekapeka, ruru and patupaiarehe, the fairy people connected with the maunga.

To complete the murals, – being painted for the Pirongia Te Aroaro o Kahu Restoration Society – key people were invited to share their stories relating to kōkako and to add finishing touches.

Gerry Kessels, a Te Pahu ecologist and society committee member was part of the team that caught the last kōkako in the 1990s to stop them dying out.

“We knew these birds were going to die in the mid-1990s, so a few Wildlife Service people with the blessing of the DoC managers decided to catch these kōkako and bring them down to Kapiti, a safe haven… was a joint effort between DoC staff and local people.”

Birds were taken to Ōtorohanga Kiwi House then flown to Kapiti Island.

Kessels has been an ecologist for 30 years.

“People say it must be so much fun being an ecologist, but the line of work I do is more like the TV programme MASH. I am up to my arms in the blood of the earth with incoming choppers just trying to fix stuff all the time. We don’t really have time to think about the bigger picture too much. We’re just trying to resolve issues as they come to the fore and avert complete catastrophe. And that’s what it’s been like for 30 years.”

He didn’t expect to see kōkako back Pirongia “so, it was a very emotional day when we first released the birds back here after 20 years, and to have them now living and breeding here.”

The Pirongia Restoration Society was formed in 2002.

“For these kōkako to come back onto the mountain there had to be a vision amongst the community that something could be done about it,” chairman Kevin Christie said.

“And the goal right from the start was to get kōkako back on the maunga. We’ve done that but it would never have happened without people like Gerry, who had the wisdom to take them away and shelter them from predators, and like Sally Uerata. She was a founding member too and our iwi representative.

North Island kōkako numbers were down to 330 breeding pairs by 1999 and it is likely the South Island kōkako is already extinct. Today that number is over 2000 pairs.

The society released 54 kōkako between 2017 and 2022, 14 of them with Pirongia genes.

“Kōkako are what we like to call an umbrella species,” Dave Bryden, who has been involved with the project from the Wildlife Permit Application stage in 2016.

“There are certain species in the forest which serve to improve the health of the forest. Kōkako can eat large fruits and therefore can spread the seeds of plant species that smaller birds cannot.”

If predator control is sufficient for kōkako to increase, the protection is being provided for all native species in the same ecosystem, he said.

See: unedited version below and get involved.

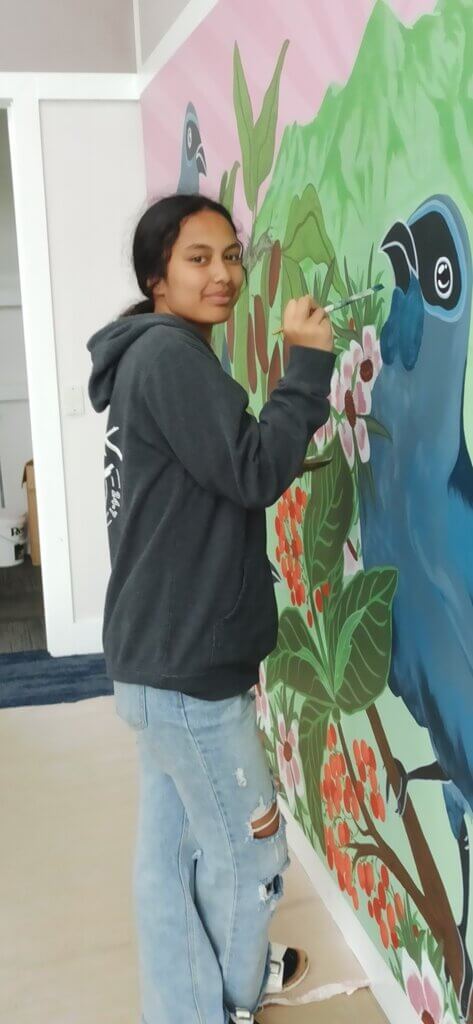

- Mihi Davis-Uerata with artist Reasha Pye. Photo: Clare St Pierre.

- Dave Bryden and Amanda Rogers banding a second generation kokako chick at Pirongia in 2021. Photo credit: Tom Davies

- Kokako ready to translocate from Pureora to Pirongia after being banded by Dave Bryden. Photo credit: Clare St Pierre

- Closeup of kokako at Pirongia. Photo credit: Bernie Krippner

- Close up of Aramoana Davis-Uerata adding touches to the kokako mural.Photo credit: Clare St Pierre

The story of kōkako at Pirongia maunga is being brought to life visually with two murals being painted for Pirongia Te Aroaro o Kahu Restoration Society at their envirocentre in Pirongia Village. Local artist Reasha Pye of ‘Tails told’ secured funding from Waipa Creative Communities for the stunning murals, one with lively kōkako feeding on Pirongia and the second an evocative night scene featuring pekapeka, ruru and patupaiarehe, the fairy people connected with the maunga.

To complete the murals, key people were invited to share their stories relating to kōkako and to add finishing touches to the murals. Three mokopuna of founding member Sally Uerata, brought a future perspective for rangatahi. Their whanau have a wonderful connection to kōkako, thanks to the Carnachan ties to Kōkakoroa Rd at Waitomo, which could be translated as ‘Plentiful kōkako’. Living at the foot of the maunga, they are close to the other stories mana whenua cherish about this sacred, spiritual bird. According to Dr Tame Roa, when King Tawhiao brought an end to the Land Wars in 1881 at Pirongia Village by laying down a substantial selection of arms, on those weapons he placed roasted tui, parrots, and wood pigeons which were foods, along with a kōkako – ‘te kōkō, te kākā, te kererū, me te kōkako’. The food offered was to remove the tapu of war, but there was a deeper message for the colonialists because of the kōkako, which was not food. These rangatahi also come from a family where hearing the waiata of the manu when they were in the ngahere on the maunga was a given, but not any longer. Their hope is the restoration of the maunga and its hei whaioranga (life force) will be a source of healing for their generation and having the kōkako back in its home will be an important part of that for Aramoana, Mihi and Maia Davis-Uerata.

Gerry Kessels, a Te Pahu ecologist and current committee member of the society was part of the team that caught the last kōkako back in the 1990s to stop them dying out.

Gerry shared about him coming to Pirongia as a young scientist with DoC in 1991:

“At that stage there was a DoC base in the village, and I stayed there in the single men’s quarters. From Pirongia to that big swathe of bush going down to Waitomo Caves there were tiny little relics of kōkako living there. We knew these birds were going to die in the mid-1990s, so a few Wildlife Service people with the blessing of the DoC managers decided to catch these kōkako and bring them down to Kapiti, a safe haven. Some of those birds also ended up north at Tiritiri Matangi Island. We spent quite a few months on it – it was a joint effort between DoC staff and local people. To catch them, we would put big soft nets between the trees, then we’d play our recorders to call the birds and egg them on into the nets. And so they’d eventually get caught in the nets and fall into a pocket of soft mesh where we could catch them. We’d calm them down, and put them in a nice bag, keep them dark and feed them things like bananas or some sugar water to relax them. Then we took them by vehicle to Otorohanga Kiwi House where they settled down, and then they were flown to Kapiti Island.

I’ve been an ecologist for 30 years and people say, “It must be so much fun being an ecologist,” but the line of work I do is more like the TV programme MASH. I am up to my arms in the blood of the earth with incoming choppers just trying to fix stuff all the time. We don’t really have time to think about the bigger picture too much. We’re just trying to resolve issues as they come to the fore and avert complete catastrophe. And that’s what it’s been like for 30 years.

I didn’t think we would ever see kōkako back on our mountain again. So, it was a very emotional day when we first released the birds back here after 20 years, and to have them now living and breeding here.”

Kevin Christie, PRS’s current Chairperson, filled in some background to Pirongia Restoration Society’s kōkako journey:

“In 2002, the Society was formed, and Clare St Pierre and I were some of the founding members. For these kōkako to come back onto the mountain there had to be a vision amongst the community that something could be done about it. We were a lot younger then and we had kids at Pirongia School that had classes in this envirocentre building (the former Pirongia School Library).

And the goal right from the start was to get kōkako back on the maunga. We’ve done that but it would never have happened without people like Gerry, who had the wisdom to take them away and shelter them from predators, and like Sally Uerata. She was a founding member too and our iwi representative. She would be telling us what it used to be like on the maunga all the time, and what we had to do. A pretty wise lady and very, very passionate. But all this is going to be passed to you. It will be your generation that will be the kaitiaki of these birds. It was only through mana whenua and the community caring about these things that have turned this around and now it is time for the next generation to take it on.

Kōkako numbers began declining with the logging by colonialists and the introduction of mammalian predators. By 1999 there were only 330 breeding pairs left and it’s likely the South Island kōkako is already extinct. But with DoC, scientists, communities and mana whenua working together numbers for North Island kōkako climbed to over 2000 pairs in 2020. PRS has released a total of 54 kōkako at Pirongia between 2017 and 2022, 14 of them with Pirongia genes.

Dave Bryden and Amanda Rogers are the kōkako ecologists have project managed the translocations and post-release monitoring. Amanda shared why they dedicate their skills towards helping the kōkako:

“This was a common bird across all our main three motu, as well as Aotea/Great Barrier Island. Waking up to the sound of kōkako should be normal – a kiwi cliche like fish and chips, not a privilege for just a few people. It should be something that we are all really familiar with, that people miss when they go overseas. I’d like to think that’s where we are going, but we’ve got a lot of work before we get there.”

They are proud of the success of the project which has seen kōkako recolonise Pirongia Forest Park and see the bird benefiting all the ecosystems there.

“Kōkako are what we like to call an umbrella species,” explained Dave Bryden who has been involved with the project from the Wildlife Permit Application stage in 2016. “There are certain species in the forest which serve to improve the health of the forest. Kōkako can eat large fruits and therefore can spread the seeds of plant species that smaller birds cannot. But if you are providing predator control which is sufficient for kōkako to increase then you are also protecting all those other native species within the same ecosystem, especially those vulnerable to rats, stoats and possums.”

“From our surveying work,” Amanda observed, “most of the kōkako at Pirongia are in areas with annual pest management, including the new Sainsbury and Kaniwhaniwha extensions, which is amazing when you consider how far they can and do roam. It means PRS chose the right places to set up pest control, which is really, really important.

Dave also emphasised that hard work and astute thinking from the society was also behind the success. “The excellent planning and strong commitment from PRS to the extensive post-release monitoring and adapting their pest control based on the monitoring feedback is now paying dividends with the growth in breeding pairs we are seeing,” he said. “This year we think we’ve just topped over 20 pairs of kōkako. So from here, hopefully it’s just going to grow at an exponential rate.”

In terms of the permit conditions, there won’t be a requirement to survey the kōkako intensively once they exceed 25 pairs, but a smaller sample could be monitored. Effective pest control will remain critically important and if people want to help support the kōkako, getting behind pest control with PRS would be a great option.

Amanda Rogers wants to see the momentum created by the project to continue: “Perhaps with the 1200 – 1300 plus hectares which PRS is protecting annually, the question might be what else could you protect? How else could you maximise the benefit of that predator control? Perhaps other species could be introduced.”

Reasha Pye wanted to inject vitality into the envirocentre to give the projects on the maunga more momentum. She has painted the kōkako to be engaging and full of personality, and was inspired to included dandelion as a food source for the kōkako by her Dad, Scott Fraser, who is a long-time volunteer for PRS: “He was there at the release of the Tiritiri Matangi kōkako at Pirongia and remembers them going for the dandelion on the lawn of the Pirongia Forest Park Lodge. That caused a lot of anxiety. The birds had obviously developed a taste for dandelion on their island home but that was pest-free and it was safe for them to eat. Here at Pirongia, there were still predators around, especially at the bush edge, so it was a relief when the birds moved deeper into the Forest Park.”

The night scene in the second mural is more about the spiritual side of Pirongia maunga.

To volunteer for Pirongia Te Aroaro o Kahu Restoration Society go to Get involved and fill in the on-line form.