Andrew Linton had just been promoted to corporal and hoped to go one better when he wrote to his parents, as Meghan Hawkes recalls in A Snip in Time from 110 years ago.

Sahara Desert. Photo: Mostafa Ft.shots. Pexels.com

“It is no easy work tramping about the Sahara Desert with a full pack on,” wrote Andrew Linton, 19, from Egypt to his parents at Mangapiko on Boxing Day, 1914.

“I have no idea how long we are to stay here. It may be till the end of the war, or we may go any time.”

Andrew was one of 11 children born to Francis and Emma Linton of Feilding. Francis, a Scotsman, was a farmer and stock dealer and the family lived in the district till around 1911 when they moved to Oeo, South Taranaki. Two years later they moved to Mangapiko.

When World War One broke out there were two Linton boys of military age, Robert – ‘Bert’- 24, and Andrew – ‘Willie’. They enlisted on 14 August, 1914.

Jessie Linton

Their sister Jessie, 26, left home around the same time to take up nursing at Thames Hospital, eventually became a sister. The brothers left New Zealand together with the Main Body in October 1914 when 10 grey-painted troopships, escorted by four warships, sailed to war. The ships carried around 8500 men, as well as nearly 4000 horses.

Andrew wrote regularly to his parents. “Five of us Te Awamutu boys went out to the pyramids and had a good look round. The workmanship in connection with the Sphinx and all the ancient temples and tombs is simply marvellous . . . On our way back we had a look through the Zoological Gardens. They are probably about the best in the world, and it would take about two days to look over properly. There is practically every kind of bird and beast imaginable there.”

By January 1915 the routines of military life had become established. “We are doing some very solid work now, tramping about the desert and digging trenches (for practice only) at night on war rations. Our butter ran out about three weeks ago . . . we have to cook all our own food. Every man has a mess tin, a sort of combined billy and frying pan. The meat was issued raw, each man having to cook his own portion. It is not the warmest place in the world for sleeping out at night, even with a couple of blankets, but it is practically mid-winter here now.”

On 25 April 16,000 Australians and New Zealanders, together with British, French and Indian troops, landed on the Gallipoli peninsula. Turkish resistance was fierce. Of the 16,000 men who landed during the first day, more than 2000 had been killed or injured by the next morning. Andrew told his parents it was “a day I am not likely to forget.”

June 1915 found Andrew in hospital with a wounded hand “which no doubt makes my writing hard to read. I was seven weeks in Turkey before I got hit, and I find they are a very inhospitable people. The fighting has been pretty fierce at times, especially on the first day we landed, but my good fortune has always stuck to me. The New Zealand nurses are in the hospital here now, and they are finding plenty to do. I saw Bert several times with the Mounteds, who are over there without their horses. He was quite well. I have been promoted to corporal already, and I hope to do better than that before I am finished. Do not trouble if you do not get letters from Bert or me regularly now, as sometimes it is very difficult to get a letter away, and the mails are not regular – they go when they can.”

Andrew Linton

By July, now “quite recovered”, Andrew observed it was “terribly hot in Egypt now, and everyone has to wear a helmet and drill suit. I shall not be sorry to get out of this country. The sand is hot enough to cook bread . . . Remember me to all Mangapiko friends, with love to all.”

Andrew was into his nineteenth week on the Gallipoli peninsula by late 1915.

“The flies are something awful – in fact, the campaign now is more against the flies than against the Turks. It is no uncommon sight to see a man sitting down and going very intently over his clothes, and he generally gets a pretty good haul of vermin. I went down to the sea last night for a swim – the first wash I have had for over a month. I saw Bert a few days ago. I expect we will be together for some time now, as the Mounteds are coming round to work with us. I am having biscuits and jam for dinner today; it’s not too bad, but I would rather have the same as you are having. However, there is a good time coming, but it is still a good way off.”

The good time, though, did not come.

Robert Charles Linton was killed in action in 1916 at the Somme, France, aged 26. Over three million men fought in this battle and more than one million were either killed or wounded, making it one of the deadliest battles in all of human history.

Caterpillar Valley (New Zealand) Memorial, Caterpillar Valley Cemetery, Longueval, Somme, France where Robert Linton’s name appears. Photo: Derrick Bunn

Andrew William Linton was wounded at the Somme and invalided to England. After recovering he was appointed Quartermaster in France. In April 1917 he rejoined his unit, and was continuously in the trenches. On 14 August, 1918 Andrew, now a sergeant, was killed while serving with the Expeditionary Forces in France, aged 23.

It was exactly four years to the day he had enlisted for war.

WW One ended at 11am on 11 November 1918, followed quickly by another enemy, a deadly influenza pandemic.

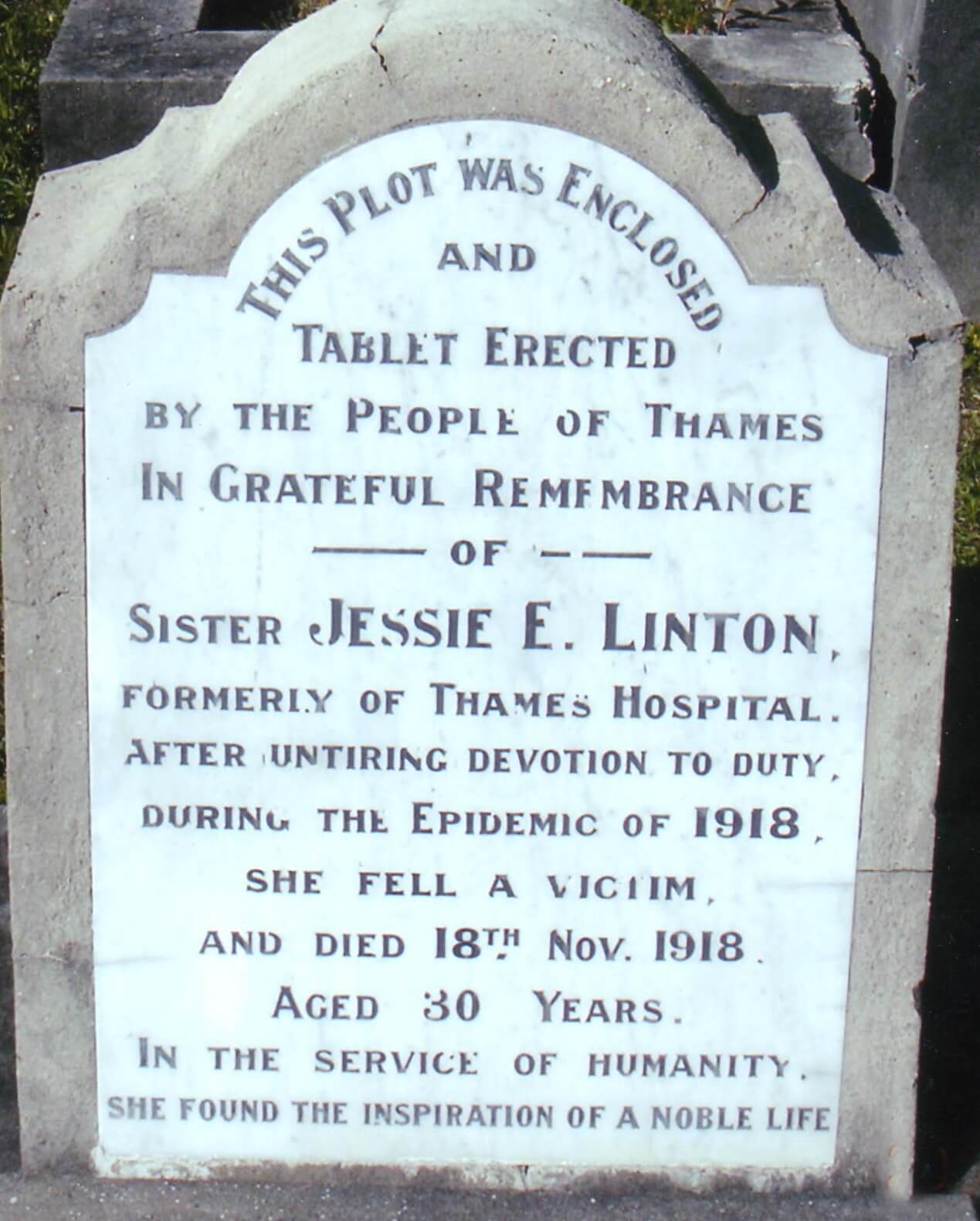

Jessie, 30, nursing at Thames Hospital, fell victim to this dying on 18 November 1918 “with startling suddenness for she was administering to the sick a few days previously and nothing of a serious nature was anticipated.”

“The Dominion,” said newspaper reports, “has lost one of its most noble workers in the cause of humanity. Her life was spent in the service of others, and she died in the same cause.”

Read: Remembering Sister Jessie Linton

The plaque on Jessies plot at Shortland Cemetery in Thames. Photo: Thames NZ Genealogy

Andrew Linton is buried at Gommecourt Wood New Cemetery, Foncquevillers, Pas-de-Calais, France. Photo: Derrick Bunn